The dramatic events of the summer of 2018-19, where a series of three mass fish kills resulted in the deaths of millions of native fish in the lower Darling-Baaka River, captured national and global attention. Feelings of sadness and horror at the scale of the fish kills had the media and general public, who for the most part had not heard of fish kills before, wondering how and why these millions of native fish deaths happened.

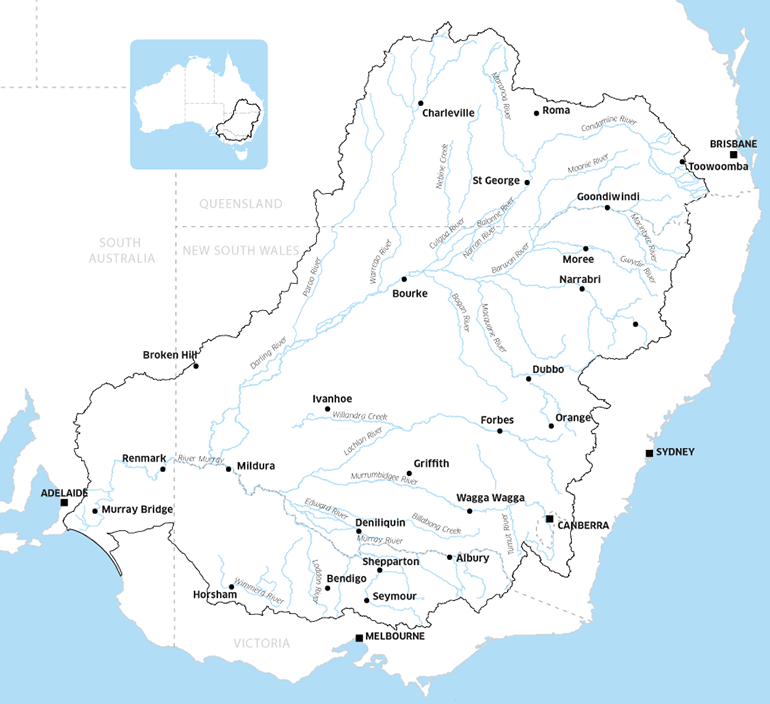

Globally, trends of fish kills occurrences are increasing, and the Murray Darling Basin is no exception. The Murray Darling Basin’s river system is highly modified, which makes it even more prone to fish kills, as the dams, weirs and infrastructure we have added to the river mean that it no longer flows freely. Unfortunately, with climate variability continuing to intensify, and regulated rivers like the Murray continuing to service a variety of needs, global trends suggest fish kills will be an ongoing water management issue.

What are fish kills exactly?

Fish kills are a natural occurrence in Australia and worldwide, and can arise from both natural and manmade causes. Fish kills are not uncommon in the Murray Darling Basin, where over 60 fish kills were reported during the 2019-20 summer.

Most fish kills occur as a result of fluctuations in the natural environment. A common cause of fish kills is algal blooms, which cause water quality issues like low oxygen or toxins that make fish unable to survive in the river. Fish kills can also be caused by single factors such as poison in the waterway or an unexpected temperature shock, or by a combination of stressors that create an uninhabitable waterway. These stressors could include hot temperatures, low water flows and low dissolved oxygen in the waterway.

The 2018-19 fish kills in the Lower Darling-Baaka River were caused by low levels of water flow creating stagnant water, which is susceptible to blue-green algae infestation. The blue-green algae absorbs the oxygen in the stagnant water as it sinks to the bottom of the river pond. Deoxygenated water is not a viable living condition for fish and resulted in many fish not being able to survive in the changed habitat.

Although fish kills are a natural environmental response to changes in weather patterns, like drought, flood or temperature shock, they can cause significant damage to native fish populations that are already endangered from other threats. Fish kills can make the existing status of threatened fishes worse by limiting their recovery progress and reducing habitat stretches that are available to them.

So what can we do?

Dr John Koehn, a freshwater fish ecologist at the Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, has shared research and recommendations about how we can improve the way we manage, evaluate and assess fish kills. John has recently been awarded a Public Service Medal for his service and important contributions to conservation and freshwater management, including this work on fish kills management.

Integrating values

The study found that integrating local community values into fish kill response strategies was one of the most important ways to improve how we manage and assess fish kills. These values include the social, recreational, economic and Indigenous cultural values that communities rely on the river and native fish for. The study found that including these values in management and response strategies can help involve the community in responding to fish kills, which provides additional support to local fish and water managers when responding to fish kills.

Establishing response protocols

To improve fish kill assessments and reporting, we need to incorporate rigorous assessments after fish kills to estimate the fish kill’s spatial extent, species composition, abundance, size and age structure, and causes. These assessments must also include the losses to ecological, scientific, cultural, social, recreational, and economic values.

John also recommends incorporating technologies like photographs, satellite images, drones and video footage to help estimate fish losses more precisely. In addition, using databases, spatial mapping and population modelling will help assess the impacts that fish kills have on native fish species. The data would be used to create a publicly accessible fish-kill tracking website with a database to keep track of fish kills and improve accountability, public communication and trust.

John also had several recommendations for short-term responses to fish kills, such as analysing the short term and long term benefits of aerators, fish rescues and stocking of native fish. Furthermore, high-risk fish kill areas, like the lower Darling Baaka River, need priority management and fish kill risk reduction strategies, along with water quality monitoring and early warning devices that alert water and fish managers when fish are at risk.

Fish kill response teams

Another recommendation is to establish dedicated fish kill response teams, which would improve the management and response to fish kills in the future. The teams would include local coordinators, data collectors, ecological experts, as well as local knowledge, water delivery and flow specialists, and fish bone collections (including otoliths – fish ear bones which can be used to track a fish’s life history).

Longer term changes

Longer-term recommendations were also found in the study, which look more broadly at fish and water management agency structures.

- Fish and water management agencies should have clear responsibilities for preventing, managing and recovery from fish kills. More resourcing needs to be allocated with the increased importance of fish kills.

- Fish population recovery plans should be developed, funded and implemented for all high-risk and affected reaches.

- We need species rescue and recovery teams and facilities for housing and breeding recovered fish (especially for small-bodied threatened species).

- Community involvement should be increased, as well as specific fish assessment and rescue training (e.g. include Indigenous, angler, conservation and local organisations).

Main Lessons

Overall, John Koehn’s study found that a philosophical change in the way people think about and manage fish kills is essential to prevent fish kills from further harming already threatened native fish populations. This involves incorporating local community members in the process of managing fish kills, making fish kill data more widely accessible and developing prevention strategies for high-risk fish kill areas. Many waterway managers have been implementing many of these lessons already and we are hopeful to see how these changes will improve fish kill occurrences and severity.

To see John’s full study and recommendations, check out his article here: https://www.publish.csiro.au/mf/Fulltext/MF20375

Featured image: A dried up Darling-Baaka River. Photo credit: Jeremy Buckingham (via Flickr)

Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode