Establishing a healthy riparian zone with all of its essential ecosystem services in an urban area is challenging. In rural zones riparian habitat is frequently improved through stock exclusion fencing, off-stream watering points, weed management and replanting of native species. In urban areas, however, numerous small properties often border the waterways, and landowners are frequently reluctant to use their valuable waterside land for riparian vegetation. Additionally, footpaths, roads, community parks and picnic areas further limit the potential extent and width of the riparian zone.

The section of Myall Creek passing through Dalby in southern Queensland, typifies many inland urban creeks. Edward Street Weir was constructed to provide a permanent pool of water, with the streambanks a mixture of private residences, roads, parklands and walking trails. A significant proportion of the bankside land is managed by the Western Downs Regional Council (WDRC) as parkland, and this is where our activities were focussed.

The fish assemblage in Myall Creek was limited in abundance and diversity, as was the instream habitat and riparian vegetation. In 2013, a restoration project commenced as part of the Dewfish Demonstration Reach, to restore the native fish populations and aquatic health in this section of Myall Creek.

Initial intervention activities targeted improving stream geomorphology and bottom roughness. Dredging and the introduction of snags and boulders created a variety of depth contours and standing structure into an otherwise relatively homogenous stretch of creek. The structural enhancement primarily benefitted larger fish species, and the response from Golden perch and Murray cod populations was positive. Unfortunately, a number of blackwater fish kills and lack of flow impacted these species and confounded results.

Little response was observed in the numbers of smaller-bodied native fish following these intervention activities, with the lack of aquatic and bankside vegetation was identified as the likely limiting factor. Our research team talked to WDRC about how such vegetation could be improved by leaving an unmown buffer strip along the water’s edge. This approach would enable the vegetation to overhang and grow out into the water, whilst having minimal impact on the amenity of the adjacent parklands. There was no cost to implement the buffer zone, and it could potentially reduce the labour involved in the maintenance of the parks.

In conjunction with the unmown buffer zone, students from Our Lady of the Southern Cross College in Dalby propagated a number of important aquatic and riparian plant species which were then planted in a degraded area of Myall Creek.

Since the buffer zone was implemented there have been significant, ongoing improvements in the quantity and variety of aquatic vegetation in Myall Creek. Leaving a 1 metre unmown buffer has resulted in bank side grasses, sedges and other low vegetation becoming much more prominent. Water primrose became far more plentiful at the site, extending into the water and providing excellent fish habitat.

In the unmown buffer there has also been a 10-fold increase in the number of native tree saplings appearing, compared to when the area was mown to the water’s edge. This natural regeneration eliminates the need for trees to be planted. As they grow the trees will help bind and stabilise the banks, providing natural structural complexity to the waterway.

The cumulative impact of the intervention activities has seen significant improvements in the condition of both the fish assemblage and habitat, with the riverbank trending towards those seen at more pristine sites.

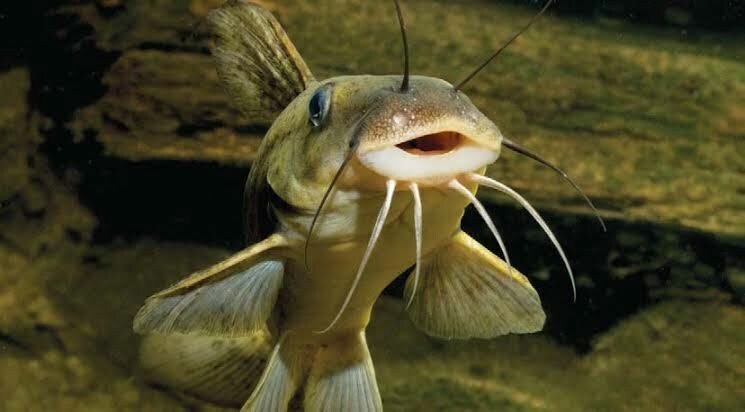

The improvement in aquatic vegetation has improved native species richness, with significant increases in the abundance of carp gudgeon, Bony bream, Murray River rainbowfish, Eel-tailed (or Freshwater) catfish and Hertyl’s catfish (Figures 1-2). Since the vegetation has returned, the number of carp gudgeons is now similar to the pristine Durah Creek reference site, and the abundance of Murray River rainbowfish and Bony bream is considerably higher. Both catfish species are using the aquatic vegetation, and there is evidence of successful recruitment occurring for the first time.

The growth of aquatic vegetation also helped smaller native fish better survive blackwater fish kills. Carp gudgeons appear to be a key indicator species for the health of smaller waterways. Tributary sites with good habitat typically have very high numbers of this species, whilst they are less common where the habitat is poor.

The improvements in habitat and the fish assembly resulting from changes in land management practice at Myall Creek have the potential to be replicated at other urbanised sections of waterway. This project provides an ideal demonstration of how taking time to have a conversation, and finding simple changes to the way things are done, can result in great benefits to aquatic ecosystems with little or no impact for nearby residents.

Partners:

Major funding has been provided by Arrow Energy, Murray-Darling Basin Authority, Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, and Condamine Alliance. The Western Downs Regional Council are also commended for their role in this project.

To read this and other great stories like it, you can purchase or download a copy of RipRap 39 magazine.

Related stories:

Deniliquin Lagoons Community Restoration Project – Bringing Back Wetland Warriors

Queensland’s Dewfish Reach installs irrigation screens to save our native fish

Dewfish Demonstration Reach

A pdf version of this story is also available to download here.