The Summer of 2018-19 saw horrendous sights in the Darling River, around 1 million fish dead from the river’s degradation. This sparked a study in 2020 by researchers Dr Martin Mallen-Cooper and Dr Brenton Zampatti from CSIRO and Charles Sturt University (Restoring the ecological integrity of a dryland river: Why low flows in the Barwon–Darling River must flow), which looked at solutions for bringing life back to the Barwon-Darling River catchment.

The mass fish kill is linked to extremely low levels of water flow creating stagnant water, which is susceptible to blue-green algae infestation. The blue-green algae absorbs the oxygen in the stagnant water as it sinks to the bottom of the river pond. Deoxygenated water is not a viable living condition for fish and resulted in many fish not being able to survive in the changed habitat.

The Barwon-Darling River is an intermittent dryland river, home to 22 native fish species and 6 introduced species. The river has historically had huge variations in flows, ecology and hydrology, with drought periods often creating low flow periods or even times with zero flow between parts of the rivers. Under natural conditions, the Barwon-Darling River flows 92% of the time, making it near-perennial (meaning it almost flows for the entire year), even during drought periods. A look at the river’s flow between 1880-1960, prior to water regulation mechanisms, shows that zero flows also occurred during drought periods which could last for 1-3 months on average.

A dry Darling River with algae. Photo credit: Jeremy Buckingham | Licence

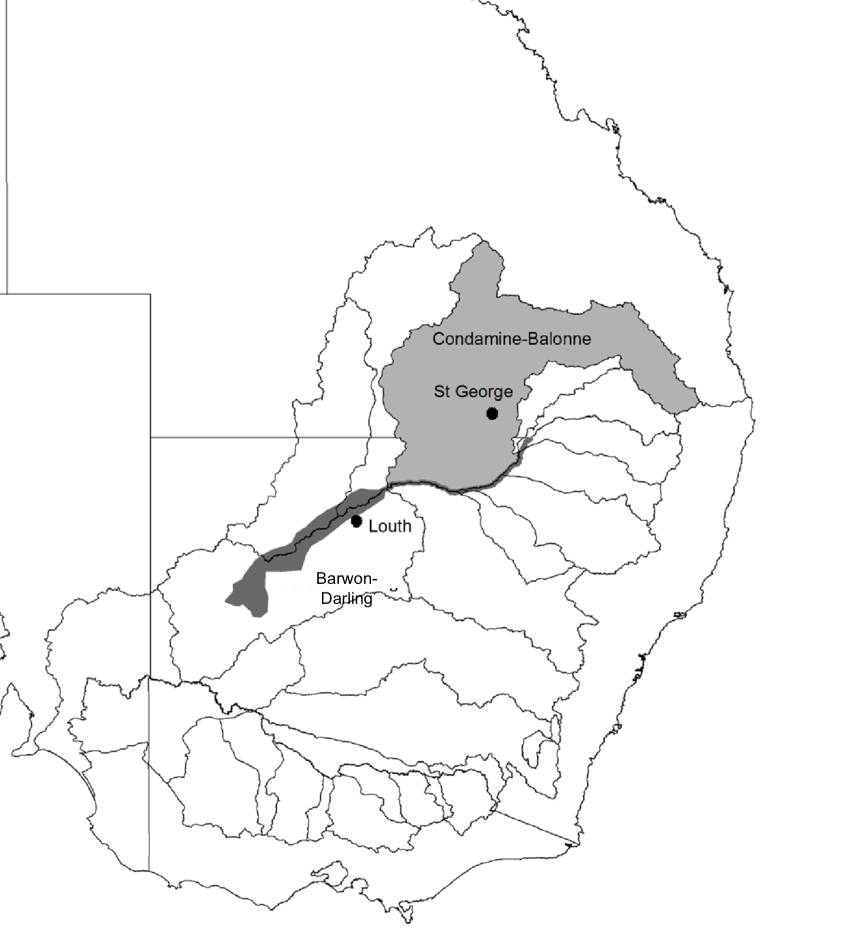

Map of Barwon-Darling river. Image credit: Brandis, Kate & Bino, Gilad. (2016). A review of the relationships between flow and waterbird ecology in the Condamine-Balonne and Barwon-Darling River systems. 10.13140/RG.2.1.2311.4484.

The Barwon-Darling River receives 99% of its flow from upstream rivers, such as the Border, Gwydir, Namoi and Macquarie rivers. This creates issues for the Barwon-Darling River as the inflow is highly dependent on the appropriate downstream release of flow from its tributaries.

Despite this variation, science shows that low flow periods and zero flows are occurring increasingly frequently. Water regulation measures, including water storage, diversion and extraction have exacerbated the river’s environmental degradation.

All these combined issues have degraded the river’s environment, modified its hydrology and fragmented the river’s ecosystem. This is highly problematic for the native fish populations that rely on the river’s flow for survival. It also presents issues for terrestrial animals and riparian vegetation that also use the river for habitat.

The 2020 study indicated that not all hope is lost for the river and its inhabitants. Mallen-Cooper and Zampatti have found 4 key solutions for fixing the river’s flow issues:

- Managing water flows using hydraulics, such as water depth, velocity and turbulence, instead of focussing on the volume of water. This means the flow can better target and restore the river’s environment for its aquatic life.

- Linking the management of upstream tributary flows to management of the Barwon-Darling catchment, to ensure enough flow reaches downstream areas.

- Providing alternative water sources for towns to prevent over-extraction during low flow periods. One of these alternatives is off-stream storage for towns that can be filled during high flow periods so the river can flow when it needs to most. These storage areas need to be covered to reduce evaporation and blue-green algae to ensure the water is secure and of a high quality.

- Removal of remote, underused weirs.

It is hoped that by applying these 4 management solutions to the river basin, the environment will see an improvement and fish kills like in 2018-19 are less likely to occur with more targeted flows.

Featured image: Fish Deaths. Photo Credit: Environment Victoria